Sooner or Later You May Have to Sell Your Favorite Stock or Mutual Fund to Sustain Your Retirement Income. With IRAs you don't have a choice.

Rationale

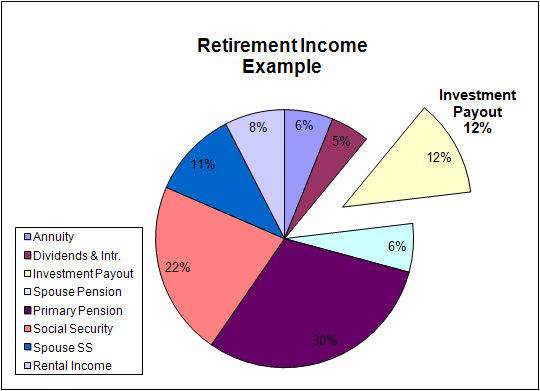

There are two main reasons when you'll need to begin selling portions of your investment portfolio(s):

- Your "regular" monthly retirement income payouts (social security, pensions, annuities etc.) are insufficient to meet your expenses, or

- You have IRAs and reached the age of 73 (or 75 starting on 1/1/2033) and are subject to IRS minimum distribution requirements.

Many people enter retirement with combinations of qualified (tax-deferred) and non-qualified investment portfolios. Qualified accounts include IRAs, 401(k)s, 403(b)s, etc., and non-qualified accounts include regular brokerage, annuities, treasuries, etc. When the need arises to begin selling assets, you should begin with your qualified investments since you’re going to have to soon (at age 73 or 75) begin selling them anyway.

The Secure Act

In December 2019, Congress passed the Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement (SECURE) Act, also known as SECURE 1.0. Later, on December 29, 2022, congress passed the SECURE 2.0 Act. This act eliminated stretch IRAs, raised the age limit for required IRA distributions, and amended other retirement tax laws. This website reflects those changes.

| Click the following link to obtain a summary of the Secure Act: | The Secure Act |

Tax Consequences of Selling Qualified Assets

Obviously there are tax consequences associated with the sale of qualified assets which will require you to pay ordinary income taxes on a portion or all of their market value. There is no way to avoid this tax. The amount that is taxed is determined by the amount (if any) of taxable contributions into the account. If all contributions were pre-tax, then you’ll be required to pay income tax on the total amount distributed.

If you plan to withdraw funds and are less than the age for mandatory withdrawals (73 or 75 years old), it pays to do a rough estimate of the impact of the distribution on your total tax obligation – i.e., will the payout bump you up into a higher tax bracket increasing the percent of taxable income?

The calculations used to determine your tax liability from the distribution are very straightforward. Start with the total value of your after-tax contributions and determine each year how much of these contributions are non-taxable income for the current year. The amount excluded from taxes each year uses up a portion of the original total value of your after-tax contributions.

Taxable Amount of Qualified Distributions

The calculation is as follows:

- Start with the original (first year) or remaining “unused” (subsequent years) taxable contribution.

- Add any contributions made in the current tax year.

- Divide this number by the total year-end combined IRA balances plus any withdrawals made in the current year.

- This yields an “after tax contribution factor”. The factor will be between 0 (no after-tax contributions) and 1.0 (all after-tax contributions and no investment growth).

- Multiply this factor by the total amount distributed (withdrawn) in the current year.

- The result is the non-taxable portion of the distribution.

- Subtract this number from the remaining “unused” taxable contribution (from step #1), yielding a reduced “unused” contribution for carryover to the next year.

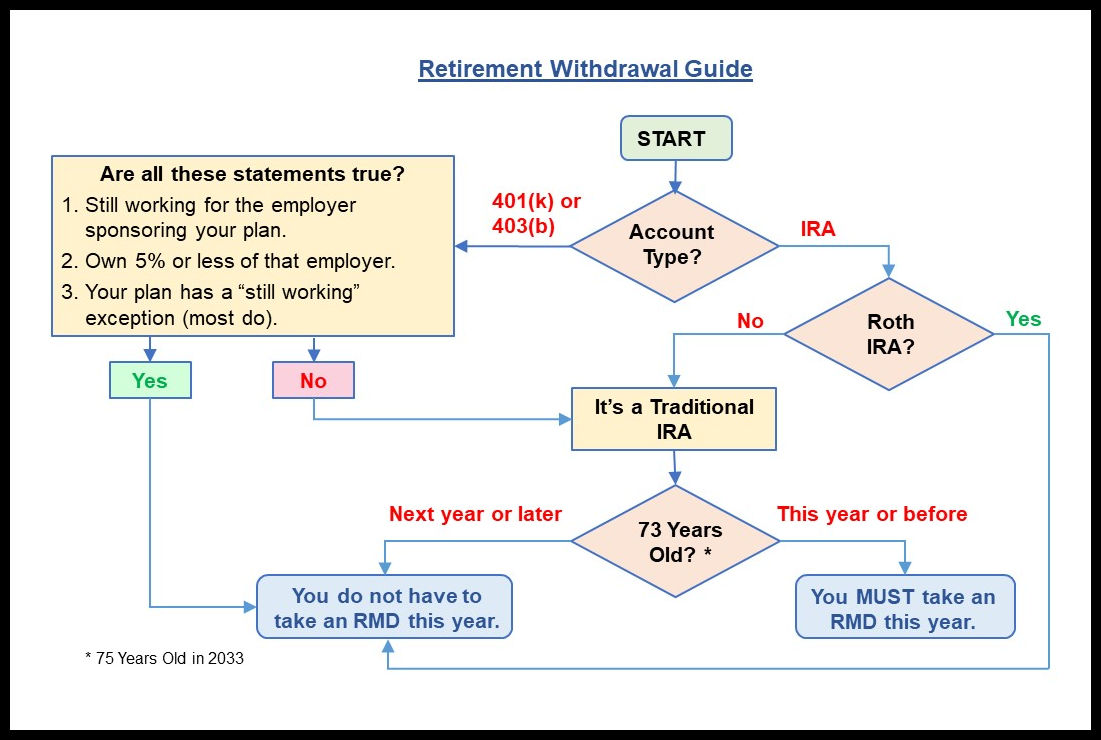

Qualified Retirement Account Withdrawal Guide

IRS Minimum Required Distributions

Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) are minimum amounts that a retirement plan account owner must withdraw annually starting with the year that they reach 73 years of age or, if later, the year in which they retire. However, for an IRA the RMDs must begin at age 73, regardless of whether the account owner is retired. Starting January 1, 2033, the first RMD must be taken at age 75.

The first RMD must be taken for the year in which they turn 73 or 75; however, the first RMD payment can be delayed until April of the following year. For all subsequent years, including the year in which the first RMD was paid by April 1st, the account owner must take the RMD by December 31st of the year.

Minimum Required Distribution (RMD) rules apply to:

- All employer sponsored retirement plans, including profit- sharing plans, 401(k) plans, 403(b) plans, and 457(b) plans.

- Traditional IRAs and IRA-based plans such as SEPs, SARSEPs, and SIMPLE IRAs.

- Roth 401(k) accounts.

- Roth IRAs after the account owner is deceased.

See the "IRA Investments page" of this website for a description of the various types of IRAs.

Although the IRA custodian or retirement plan administrator may calculate the RMD, the account owner is ultimately responsible for taking the correct amount of RMDs on time every year from their accounts, and they face stiff penalties (25% tax) for failure to take RMDs. This penalty is reduced to 10% of the RMD if corrected in a timely manner. Amounts greater than the RMDs can be taken any year, but these excess distributions do not count towards RMDs in subsequent years.

A RMD is calculated for each account by dividing the prior December 31st balance of that IRA or retirement plan account by a life expectancy factor that IRS publishes in Tables in Publication 590, Individual Retirement Arrangements (IRAs). There are three separate tables:

- The Uniform Lifetime Table is used by 1) unmarried owners, 2) married owners whose spouse is not more than 10 years younger, and 3) married owners whose spouse is not the sole beneficiary of the account owner,

- The Joint and Last Survivor Table is used by an account owner whose sole beneficiary of the account is his or her spouse who is more than 10 years younger than the account owner, and

- The Single Life Expectancy Table is used by a beneficiary of a deceased owner's account.

Uniform Lifetime Table

Following is the most commonly used table (Uniform Lifetime) from IRS Publication 590 – Appendix B (Updated in 2022):

|

Table III

(Uniform Lifetime)

For Use by:

|

|||||

|

Age

|

Distribution Period

|

Age

|

Distribution Period

|

Age

|

Distribution Period

|

|

72

|

27.4

|

88

|

13.7

|

104

|

4.9

|

|

73

|

26.5

|

89

|

12.9

|

105

|

4.6

|

|

74

|

25.5 |

90

|

12.2

|

106

|

4.3

|

|

75

|

24.6

|

91

|

11.5

|

107

|

4.1

|

|

76

|

23.7

|

92

|

10.8

|

108

|

3.9

|

|

77

|

22.9

|

93

|

10.1

|

109

|

3.7

|

|

78

|

22.0

|

94

|

9.5

|

110

|

3.5

|

|

79

|

21.1

|

95

|

8.9

|

111

|

3.4

|

|

80

|

20.2

|

96

|

8.4

|

112

|

3.3

|

|

81

|

19.4

|

97

|

7.8

|

113

|

3.1

|

|

82

|

18.5

|

98

|

7.3

|

114

|

3.0

|

|

83

|

17.7

|

99

|

6.8

|

115

|

2.9

|

|

84

|

16.8

|

100

|

6.4

|

116

|

2.8

|

|

85

|

16.0

|

101

|

6.0

|

117

|

2.7

|

|

86

|

15.2

|

102

|

5.6

|

118

|

2.5

|

|

87

|

14.4

|

103

|

5.2

|

119

|

2.3

|

An IRA owner must calculate the RMD separately for each IRA that he or she owns but can withdraw the total amount from one or any combination of the IRAs. Similarly, a 403(b)-contract owner must calculate the RMD separately for each 403(b) contract that he or she owns but can take the total amount from one or any combination of the 403(b) contracts.

However, RMDs required from other types of retirement plans, such as 401(k) and 457(b) plans have to be taken separately from each of those plan accounts.

Beneficiary's Income Tax from a Retirement Plan Distribution

Beneficiaries must include any taxable distributions they receive in their gross income. Since qualified accounts are pre-tax, any amount distributed to anyone other than the employee’s spouse is taxable as ordinary income in the year that it is distributed. This is why it's valuable to lessen the tax burden by stretching payments out for as long a period as possible.

Generally, a beneficiary reports pension or annuity income in the same way the plan participant would have reported it. However, some special rules apply.

A beneficiary of an employee who was covered by a retirement plan can exclude from income an amount equal to the deceased employee's investment in the contract (cost). If the beneficiary is entitled to receive a survivor annuity on the death of an employee, the beneficiary can exclude part of each annuity payment as a tax-free recovery of the employee's investment in the contract.

Benefits paid to a survivor under a joint and survivor annuity must be included in the surviving spouse's gross income in the same way the retiree would have included them in gross income.

Using Qualified Distributions

Once the distribution from your qualified account is taxed, it can be either spent or reinvested. However, it cannot be reinvested into a new or other qualified account.

If you do not need any or a portion of the required distribution, you should reinvest it. Withdrawing money from your qualified investment account reduces the account’s value and possibly, depending on growth, the amount of future distributions. Therefore, it is advantageous to reinvest as much of the distribution as you can to preserve your future income.

The best investment for your money depends on the state of the stock market at the time that the distribution is made.

Selling Qualified Investments at Market Bottom

If the distribution occurs at a time when stock and mutual fund values are historically low, you should consider reinvesting the proceeds in the stock market. Your reinvestment in a non-qualified brokerage account enables you to preserve the value of your investment – you are compensating your “selling low” transaction(s) by “buying low”.

In fact, you can repurchase the same mutual funds or stock outside of the qualified account that you just sold within the account. Since you are paying taxes on the full market value of the investments sold, “wash sale” rules (see below) are not relevant. Therefore, you can have the same income-producing asset that you previously had, except that you may elect to purchase fewer shares in order to cover the income tax due.

As mentioned in the Retirement Investing section of this website, I’d recommend purchasing quality dividend stocks rather than mutual funds. The dividends from these stocks will add to your monthly income, and you won’t be incurring annual capital from just holding these shares. As mentioned earlier in this website, mutual funds are required to make regular distributions of capital gains to their shareholders, so you may have capital gains taxes to pay even if you never sold any of your mutual funds.

Selling Qualified Investments at Market Top

If the distribution occurs when stocks and mutual funds are being traded at high values, then you may wish to preserve the cash value of your withdrawal by purchasing CDs or bonds. If you already have CDs, select maturity dates that ensure a steady stream of future income – i.e., use the CD laddering technique described in the Retirement Investing Section of this website.

Selling Non-Qualified Investments

There may come a time in your retirement when you’ve depleted your qualified investment accounts and need to begin selling stock and mutual funds from your non-qualified (after tax) account(s). When you sell stocks or mutual funds at a profit, those profits are known as capital gains.

The tax rate you'll pay on your capital gains depends on whether they are long-term (you held the security for longer than 12 months) or short-term (you owned the stock for 12 months or less). To determine how long you held the asset, count from the date after the day you acquired the asset up to and including the day you disposed of the asset.

Capital gains and deductible capital losses are reported on Form 1040, Schedule D. If you have a net capital gain, that gain may be taxed at a lower tax rate than your ordinary income tax rates. The term "net capital gain" means the amount by which your net long-term capital gain for the year is more than the sum of your net short-term capital loss and any long-term capital loss carried over from the previous year.

Generally, a net capital gain is taxed at a rate no higher than 15%. However, for the years 2008 through 2012, some or all of your net capital gain may be taxed at 0%, if it would otherwise be taxed at lower rates. There are three exceptions where capital gains may be taxed at rates greater than 15%, but they are not applicable to the type of transactions discussed here.

If you have a taxable capital gain, you may be required to make estimated tax payments. Refer to Publication 505, Tax Withholding and Estimated Tax, for additional information.

If your capital losses exceed your capital gains, the amount of the excess loss that can be claimed is the lesser of $3,000, ($1,500 if you are married filing separately) or your total net loss as shown on line 16 of Form 1040 Schedule D, Capital Gains and Losses. If your net capital loss is more than this limit, you can carry the loss forward to later years. Use the Capital Loss Carryover Worksheet in Publication 550 to figure the amount carried forward.

If you have a lot of capital gains, it can make sense to look at your portfolio at year end and sell shares just to generate a loss for tax purposes. If it's a stock or fund that you really want to own, you can buy it back later, but this is where the “wash sale” rules come in.

Wash Sale Rules

Under the wash sale rules, if you sell stock or mutual funds for a loss and buy them back within the 30-day period before or after the loss-sale date, the loss cannot be immediately claimed for tax purposes. The disallowed amount (capital loss) is however added to the cost of the repurchased stock.

The IRS rule includes not only the same security but one that is "substantially identical”. The "substantially identical" rule means that you can't take a tax loss and buy a mutual fund within 30 days if the new fund is essentially the same as the fund you sold. In other words, you can't sell one S&P 500 index fund and repurchase an S&P 500 index fund from another company the next day and still take the tax loss.

If you violate any of the provisions of the wash sale rule, your loss will be disallowed.

There are a couple of other points you should consider on the topic of wash sales:

- First, a risk of selling a stock or mutual fund that you really like just for tax purposes is that the share price may increase significantly in the 30 days, and you'll have to buy back the shares at a higher price than you sold them.

- Secondly, tax-loss selling only makes sense in taxable accounts. Because your IRA or 401(k) plan already has tax advantages, there's no reason to sell at a loss just to offset any gains!

And remember this cardinal rule of tax selling: you'll never get rich taking tax losses!

Distributions Upon Owner's Death

As shown in the Estate Planning section of this website, it's very important for you to designate appropriate beneficiaries to your qualified investment accounts. If married, your spouse should be designated as primary beneficiary with your living trust or children usually designated as secondary or contingent beneficiaries. Beneficiaries are designated under procedures established by the plan.

After the death of the account owner, beneficiaries of retirement plan and IRA accounts have the option of taking a lump-sum distribution of the inherited account at any time. Otherwise, they are subject to required minimum distribution (RMD) rules. These rules vary by whether the account is a Roth IRA and whether the designated beneficiary is an “eligible beneficiary” defined as:

- Spouse,

- Minor child of the deceased account holder,

- Disabled or chronically ill individual, or

- Individual who is not more than 10 years younger than the IRA owner or plan participant.

Spousal beneficiary options.

The spouse of the account owner has more options than non-spouse beneficiaries if they're the sole beneficiary. Determination of whether the spouse is the sole beneficiary is made by September 30 of the year following the year of the account holder's death.

For the year of the account owner's death, the RMD due is the amount the account owner was required to withdraw and did not withdraw before death, if any. Beginning the year following the owner's death, the RMD depends on certain characteristics of the designated beneficiary and the distribution option chosen by the beneficiary.

If the account holder's death occurred prior to the required beginning date for required distributions, the spouse beneficiary may:

- Option #1: Keep as an inherited account delaying distributions until the employee would have turned 72, take distributions based on their own life expectancy, and follow the 10-year rule (as defined below).

- Option #2: Roll over the account into their own IRA.

If the account holder's death occurred after the required beginning date, the spouse beneficiary may: 1) Keep the IRA as an inherited account and take distributions based on their own life expectancy, or 2) rollover the account into their own IRA

Eligible Non-spouse beneficiary options.

Options for a beneficiary who is not the spouse of the deceased account owner depend on whether they are an "eligible designated beneficiary." An eligible designated may:

- Take distributions over the longer of their own life expectancy and the employee's remaining life expectancy, or

- Follow the 10-year rule (if the account owner died before that owner's required beginning date)

The 10-year rule requires the beneficiary to empty the entire account by the end of the 10th year following the year of the account owner's (or eligible designated beneficiary's) death.

Designated ineligible beneficiary.

If the beneficiary is an individual, they must follow the 10-year rule whereas beneficiaries that are not individuals are subject to the 5-year rule:

- They must empty account by the end of the 5th year following the year of the account holders' death.

- No withdrawals are required before the end of that 5th year.

Inherited Roth IRAs

Generally, inherited Roth IRA accounts are subject to the same RMD requirements as inherited traditional IRA accounts. Withdrawals of contributions from an inherited Roth are tax free. Most withdrawals of earnings from an inherited Roth IRA account are also tax-free. However, withdrawals of earnings may be subject to income tax if the Roth account is less than 5-years old at the time of the withdrawal. Distributions from another Roth IRA cannot be substituted for these distributions unless the other Roth IRA was inherited from the same decedent.